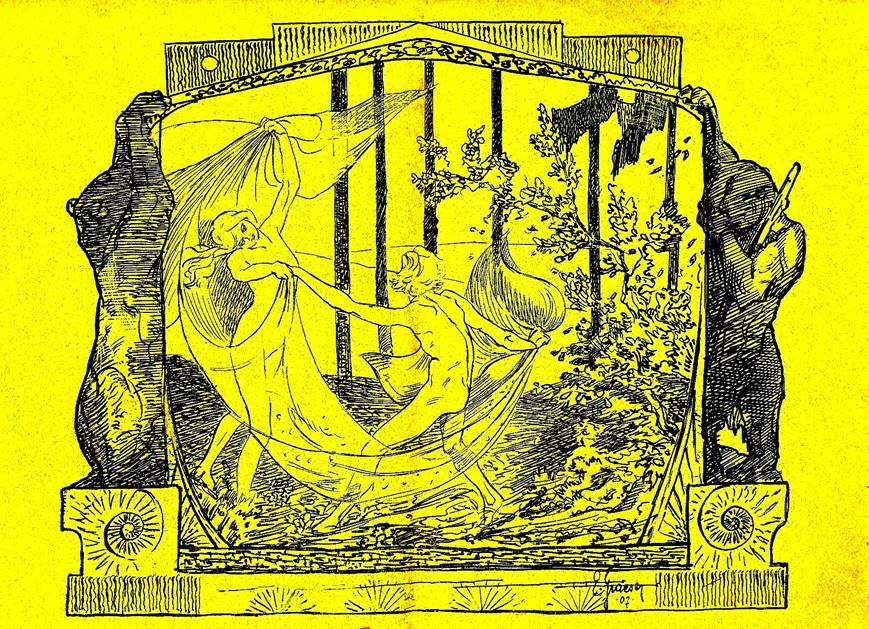

Frühlingsweben

Zeichnung von Ernst H. Graeser

| Ernst Heinrich Graeser (1884-1944), der jüngste der drei Gräserbrüder, studierte Malerei in München und Stuttgart. Zwischen 1903 und1911 lebte er immer wieder, für länger oder kürzer, bei seinen Brüdern auf dem Monte Verità von Ascona. Im Winter 1906/7 machte er in Locarno eine Ausstellungseiner Gemälde. Zu den Käufern seiner Bilder zählte auch Hermann Hesse. Ernst Heinrich, der später ein Anhänger von Rudolf Steiner wurde, stand damals unterdem Einfluss von Karl und Gusto. Dies belegen u. a. die Erinnerungen des ehemaligen Erzherzogs Leopold von Toskana, später Leopold Wölfling genannt, derselbst zeitweise ein „Naturmensch“ bei den Gräsers in Ascona gewesen war. Wölfling nennt die Gräsers in seinem Buch nicht beim Namen, er nennt sie„Vögel“, wohl in Anlehnung an „Wandervögel“. Nach den beiden „Vögeln“ Karl und Gusto ist für ihn Ernst „Vögel the Third“. | Ernst

Heinrich Graeser (1884-1944), the youngest of the three

Gräser brothers, studied painting in Munich and Stuttgart.

Between 1903 and 1911 he repeatedly lived, for longer or

shorter periods, with his brothers on Monte Verità in

Ascona. In the winter of 1906/7 he held an exhibition of his

paintings in Locarno. Hermann Hesse was one of the buyers of

his paintings. Ernst Heinrich, who later became a follower

of Rudolf Steiner, was then under the influence of Karl and

Gusto. This is evidenced by the memoirs of the former

Archduke Leopold of Tuscany, later called Leopold Wölfling,

who himself had been a "nature person" at times with the

Gräsers in Ascona. Wölfling does not call the Gräsers by

name in his book, he calls them "Vögel" (birds), probably in

reference to "Wandervögel" (migratory birds or rather

excursionists). After the two "birds" Karl and Gusto, Ernst

is for him "Vögel the Third". |

Vögel the Third

by Leopold Wölfling

To rid the world of sex! This

had been the battle cry of each Vögel [Gräser] in turn. But as I

listened to its exposition by Vögel the Third [Ernst Gräser], I was

considerably more impressed by the possible sanity of this

back-to-natue creed than when its tenets were shrieked at me in the

hysterical vaporings of his unbalanced brothers and sister-in-law.

According to this bright young

man, the most Beautiful Thing in life, if rightly understood, was Sex.

But through the degeneracy and perversion of modern civilized ideas,

this Beautiful Thing had been degraded until its Beauty was no longer

recognizable. It throve as a festering canker in the lives of men and

women.

Our young friend held that

clothes were an abomination because they created in us an unhealthy

curiosity and element of mystery which resulted in the morbid

perversion of our natural sex instincts. (193) …

„What is more beautiful than

the nude human form?“ argued Vögel the Third. „Take those old-lady

Philistines of the past who, driven by moral indignation to wrap their

shawls round what they conceived to be indecent statues of nude

figures. What was the result of the so-called pious act? Merely to

increase the evil of lasciviousness which they

thought to hide. At Ascona we believe clothing to be a fetish

wich destroys healthy human passion, degrading it to vice.“

To me this seemed rather a

good line of talk, and the young man gradually interested me more and

more in his theories. I found this companionship so stimulating that I

was quite sorry when, after making himself a very unobtrusive member

of our household for nearly a moth, he returned to Ascona. …

Somehow I bamboozled myself

into the belief that this back-to-nature cult also included serious

thinkers like Vögel the Third, and if these more sanely-balanced

members of the colony were really in earnest, I began to feel that it

would be a highly diverting adventure to live among them for a while

and observe at first-hand how their no-clothes experiment worked out.

(194).

Of the Moonlight Revels, I

was, of course, a distinctly interested spectator, for I felt that I

could now test how far the theories on Sex, so eloquently propounded

by Vögel the Third, were sound. What this apparently earnest student

of the problem had said in affect was that sex evils would vanish if

men and women could but grow accustomed to looking on one another

naked without feeling ashamed.

„Why, if confronted by an

unknown male, should a naked woman at once feel guilty and seek to

cover herself up, if not to run away and hide?“ had been one of the

conundrums this young man had thrust at me, and he had laughed me to

scorn when for answer I said: „ A woman in such circumstances seeks to

hide herself from a man for the same reason as she screams in terror

whenever she sees a mouse. A self-protective instinct, given to her at

the Creation, compels her to act in this way.“ (201)

„How do you know what Woman

felt towards Man at the Creation?“ he had scoffed. “I contend that her

self-protective instinct, as you call it, was not with her at the

start, but has been imposed on her by a trick of the devil in inducing

her to wear clothes. This so-called instinct would never have been if

only through the ages men and women had faced each other fairly and

squarely in a state of simple nature rather than with covered bodies

in mock modesty and shame.“

Here, then, at these Moonlight

Revels I could now see if this strange theorist were right. Alas! As I

looked on, I could only decide that he was most hopelessly wrong. To

the strains of reed-like gipsy music, borrowed from Hungary and not

with a certain allure itself, never had I seen so unalluring a sight

as this set of thin-limbed men and knock-kneed women, now gyrating

about this open field stark naked in the moonlight. They imagined that

they danced, but truly, there was neither rhythm nor reason about

their dancing at all. They contorted themselves this way and that.

Their gestures, far from being beautiful, seemed ugly, formless, and

insane. (201)

My ultimate conclusion about

this mad spectacle was that, let Vögel the Third argue as he would,

this uncovering of the human body by no means made for Sex-innocence.

I admit that through having lived together in the nude, cheek by jowl,

for so long, these strange human madcaps seemed now able to look on

one another without the slightest Sex-thrill. But since many of them

wore spectacles and pince-nez, even though they were undressed, what

else could you expect?

Still, here and there, one

caught glimpses of human forms less anaemic in energy because they

were more athletic in build. But what young Vögel mistook in the

latter for Sex-innocence was in reality Sex-apathy, a state contrary

to Nature, which inflicts terrible punishment on all who fall into it.

Never shall I forget the lustreless eyes with which these more

vigorous men and women of this back-to-nature colony regarded one

another as, uttering silly, raucous cries, they capered about in the

moonlight. In their efforts to get back to Nature, they had run away

from her altogether.

To me, the most repellent part

of their capers was that each one of the caperers seemed to enjoy

himself best when capering alone. Each seemed to like best to indulge

in solo dances. Each appeared positively to recoil from touching

another. Comradeship or any other human feeling between these people,

apart from spleen and jealousy, was dead. Their state of nudity had

killed it. In a word, they were megalomaniacs. Instead of living for

each other, they lived simply for themselves. (202)

After a week of sheer misery at the back-to-nature colony I returned with my wife to Zug. (204)