Harold

Monro (1879 - 1932)

Harold

Monro (1879 - 1932)

English see below

In

'Beyond New Age. Exploring Alternative Spirituality'. Herausgegeben

von Steven Sutcliffe und Marion Brown, Edinburgh University Press,

Edinburgh 2000, schreibt Martin Green unter dem Titel 'New Centres of

Life':

"Einer der wenigen Engländer, die in jenen Jahren vor 1914 in Ascona lebten, war Harold Monro, der später viele Jahre lang den Poetry Bookshop in London leitete, ein Zentrum der modernen Poesie in England. Während seiner Sommer in Ascona arbeitete er an einem langen Gedicht mit dem Titel "Jehova", in dem er die Figur des Gottvaters angriff. Monro besuchte die Whiteway-Kommune in den Cotswolds, eine englische Version von Ascona, von der später die Rede sein wird; und bei einem von Edward Carpenters Besuchen in Florenz reiste Monro von Ascona an, um mit ihm zu sprechen" (55).

In 'Prophets of a New Age'. New York, Toronto, Oxford 1992, schreibt Martin Green:

"Der englische Dichter Harold Monro begann während seiner Zeit in Ascona (kurz vor 1913) ein episches Gedicht mit dem Titel 'Jehova', an dem er die nächsten vierzehn Jahre arbeitete und das, den erhaltenen Fragmenten nach zu urteilen, eine ähnliche Botschaft [wie Otto Gross] gehabt zu haben scheint. Er stellte seinen Jehova als "einen unwissenden und rüpelhaften Unhold" dar, den Gott des aggressiven Nationalismus, wie der Vater im Tanz; und einige Zeilen deuten auf die Geschichte von Otto Gross hin:

"Einer der wenigen Engländer, die in jenen Jahren vor 1914 in Ascona lebten, war Harold Monro, der später viele Jahre lang den Poetry Bookshop in London leitete, ein Zentrum der modernen Poesie in England. Während seiner Sommer in Ascona arbeitete er an einem langen Gedicht mit dem Titel "Jehova", in dem er die Figur des Gottvaters angriff. Monro besuchte die Whiteway-Kommune in den Cotswolds, eine englische Version von Ascona, von der später die Rede sein wird; und bei einem von Edward Carpenters Besuchen in Florenz reiste Monro von Ascona an, um mit ihm zu sprechen" (55).

In 'Prophets of a New Age'. New York, Toronto, Oxford 1992, schreibt Martin Green:

"Der englische Dichter Harold Monro begann während seiner Zeit in Ascona (kurz vor 1913) ein episches Gedicht mit dem Titel 'Jehova', an dem er die nächsten vierzehn Jahre arbeitete und das, den erhaltenen Fragmenten nach zu urteilen, eine ähnliche Botschaft [wie Otto Gross] gehabt zu haben scheint. Er stellte seinen Jehova als "einen unwissenden und rüpelhaften Unhold" dar, den Gott des aggressiven Nationalismus, wie der Vater im Tanz; und einige Zeilen deuten auf die Geschichte von Otto Gross hin:

Devourer

of your first-born, unbeloved …

You will not claim to be the father of Jesus? …

War lords are your archangels, O Jehovah

You will not claim to be the father of Jesus? …

War lords are your archangels, O Jehovah

Das Gedicht zeigte, wie der jüdische

Monotheismus historisch die animistische Anbetung von Steinen und

Pflanzen und Wasser ersetzt. (Labans Autobiographie schreibt

Steinen, Sanden und Kristallen in seiner frühen Erfahrung eine große

Bedeutung zu.) Monro zitierte Shelley, der sagte, dass der Sturz der

Gottesvorstellung das höchste Gut der Erde herbeiführen würde.

Das Gedicht zeigte, wie der jüdische

Monotheismus historisch die animistische Anbetung von Steinen und

Pflanzen und Wasser ersetzt. (Labans Autobiographie schreibt

Steinen, Sanden und Kristallen in seiner frühen Erfahrung eine große

Bedeutung zu.) Monro zitierte Shelley, der sagte, dass der Sturz der

Gottesvorstellung das höchste Gut der Erde herbeiführen würde.Wenn wir diese drei Legenden zusammenfügen, haben wir eine Idee, ein Programm - eine Entmachtung des Menschen und seines Gottes, eine Thronbesteigung der Magna Mater -, das allen Asconanern lieb war" (35).

"Wir wissen nicht, ob sich [Edward] Carpenter jemals in Ascona aufgehalten hat, aber in den Jahren 1910 und 1911

war er in Florenz und führte lange Gespräche mit Harold Monro, der

ein Haus in Ascona besaß und zwischen dort und Florenz hin und

her pendelte. Monro war später Inhaber des Poetry Bookshop in London

und Förderer der zeitgenössischen Poesie in England. Er hatte sich gerade von

seiner Frau getrennt und bekannte sich zu seiner Identität als

Homosexueller" (53).

"So diskutierte A Modern Utopia [von H. G. Wells] mit

seinem Tessiner Schauplatz eine hypothetische Gesellschaftsordnung

moderner Samurai, basierend auf den Samurai Japans. Dies inspirierte

Harold Monro und einen Freund, einen Orden des freiwilligen Adels zu

gründen und eine Presse, um Bücher zu drucken, die dieser Idee

gewidmet waren. Dies war eine asketische New-Age-Idee. Die Samurai

sollten Keuschheit, Vegetarismus und frühes Aufstehen praktizieren,

auf Alkohol und Rauchen verzichten und einige Tage im Jahr in Fasten

und Meditation verbringen. Wells kam zu einigen ihrer Treffen" (56).

|

Von H. G. Wells zu Harold Monro

|

"Wir haben Dr. Skarvan getroffen, der sowohl in Ascona als auch in der Kirche der Tolstojanischen Bruderschaft in Croydon Zeit verbrachte, wo Leute eine weitere solche Kolonie planten. Harold Monro besuchte die Whiteway-Kolonie in den Cotswolds, die von den Croydon-Tolstojanern gegründet wurde. Etwa zur gleichen Zeit besuchte auch Gandhi Whiteway" (79).

Dass Monro die Ideen von Friedrich Nietzsche und Otto Gross, also die asconesischen Ideen, aufgenommen und weitergetragen hat, dafür spricht u. a. das folgende Gedicht. Monro spricht aus, was unsre tiefste Sorge ist und sein muss.

To what God

To what GodShall we chant

Our songs of Battle?

Oh, to whom shall a song of battle be chanted?

Not to our lord of the hosts on his ancient throne,

Drowsing the ages out in Heaven alone.

The celestial choirs are mute, the angels have fled:

Word is gone forth abroad that our lord is dead.

Is it nothing to you, all you that pass by?

Behold and see if there be any sorrow like unto my sorrow.

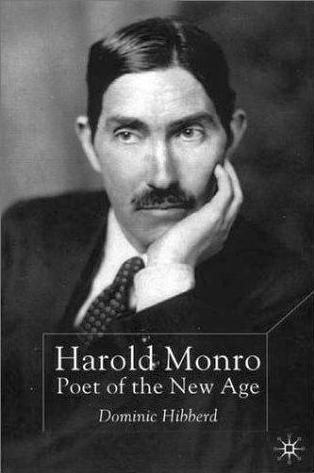

Eine Verlagsanzeige sagt über Monro:

"Troubled by

his complex sexuality, Monro was a tormented soul whose aim was to

serve the cause of poetry. Hibberd's revealing and

beautifully-written biography will help rescue Monro from the

graveyard of literary history and claim for him the recognition he

deserves. Poet and businessman, ascetic and alcoholic, socialist

and reluctant soldier, twice-married yet homosexual, Harold Monro

probably did more than anyone for poetry and poets in the period

before and after the Great War, and yet his reward has been near

oblivion. Aiming to encourage the poets of the future, he

befriended, among

many others, T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound and the Imagists; Rupert

Brooke and the Georgians; Marinetti the Futurist; Wilfred Owen and other war poets; and the noted women

poets, Charlotte Mew and Amma Wickham. Monro was the founding

editor of three leading periodicals, including The Poetry Review,

and was responsible for the ground-breaking anthology Georgian

Poetry."

März

1910.

Der englische Dichter Harold Monro zieht von einem Landhaus in Locarno erst auf den Monte Verità, später in die Mühle von Ronco.

Der englische Dichter Harold Monro zieht von einem Landhaus in Locarno erst auf den Monte Verità, später in die Mühle von Ronco.

Harold Monro pp 57-70

Pilgrimage to Freedom 1908 – 9

Dominic Hibberd

Abstract

Having failed

to find the modern Utopia in Surrey, Harold was to spend the next

few years looking for it on the Continent. The narrator of Wells’s

book had found it while walking in the mountains of southern

Switzerland, later discovering that solitary long-distance walks

were an essential part of the Samurai discipline. Harold decided

his own search would start with a ‘pilgrimage’, a journey of the

soul through snow and hard weather to the ever-returning spring.

He would walk to Italy, the land Maurice had dreamed of, hoping

the rigours of the way would clear his mind and help him to see

his own and the world’s ‘great wonderful future’. And in some

strange way it worked. His old life of social conformism, sexual pretence

and literary pastiche was left behind for ever.

Pilgrimage to Freedom 1908 ± 9

Joy of the hero in his motion showed:

He moved the clear ways of the earth along,

And to the daylight of the orient strode.

He moved the clear ways of the earth along,

And to the daylight of the orient strode.

('Two Visions')

Having

failed to find the modern Utopia in Surrey, Harold was to spend the

next few years looking for it on the Continent. The narrator of

Wells's book had found it while walking in the mountains of southern

Switzerland, later discovering that solitary long-distance walks

were an essential part of the Samurai discipline.

Harold decided his own search would start with a `pilgrimage', a journey of the soul through snow and hard weather to the ever returning spring. He would walk to Italy, the land Maurice had dreamed of, hoping the rigours of the way would clear his mind and help him to see his own and the world's `great wonderful future'. And in some strange way it worked. His old life of social conformism, sexual pretence and literary pastiche was left behind forever. He made final preparations in Paris, sending his heavy luggage ahead to Milan and arranging for mail to be forwarded to post offices along his route. After much repacking he got his knapsack down from 21 lb. to 15 lb., reluctantly leaving out More's Utopia and Keats but keeping Shakespeare and Emerson.1

He also took his diary, intending to use it for some sort of publication later. A photograph taken before another of his long walks a year or two later shows him dressed most uncomfortably by today's standards, equipped with only a walking stick and rain cape (Plate 10). He probably looked much the same when he left Paris, ready for a walk of nearly 600 miles. He decided to let his beard grow as a gesture of liberation. The walk began from Paris on 1 April 1908. He made for Fontainebleau, where he spent three days, his mother arriving on the 5th to fuss over him and sew on missing buttons. For the next few weeks he walked steadily south-east, averaging some fifteen miles a day, often in rain. He preferred roads to rough country, enjoying the freedom to look around him and keep up a regular stride. Cars were still rare, but when motorists passed they stared in puzzled amusement, France having not taken up the new German-Swiss fashion for hiking. The further he went from Paris the kinder people became, but the more they regarded him as a lunatic. Sometimes a boy would trot along beside him, asking questions; once he was checked by the police. In the mornings he often wrote for several hours, but then he would walk without pausing except for a lunch break, unless the weather was especially bad. Occasionally even lunch was omitted, and he would fast for ten hours or more, convinced it did him good. Sometimes he walked on until the moon rose; it was by moonlight that he entered the hilltop `dream-city' of Flavigny, silent within its ancient walls, and slept on the inn landing, pestered by fleas. Many of the villages and little towns had medieval gates and splendid churches; often some great spire or ruined castle would seem to dominate the horizon all day. The hotels were cheap, damp and grubby, but they provided friendly company in the evenings, when mill hands, railway porters, commercial travellers and soldiers would tell him about poverty in France and ply him with too much wine. When spring broke among the vineyards of the Côte d'Or with a flourish of butterflies and the sound of a cuckoo, he felt `the first thrill, that vernal quickening of the blood, . . . the most beautiful sensation of the year'. People kept warning him of brigands, so at Dijon he bought a revolver, soon cursing its useless weight. As he approached the high plateau of the Jura the weather reverted to winter, with some snow. Locals suggested a diversion to Baume-les-Messieurs to see the caves and a genuine hermit; a storm trapped him there for two nights, swelling the famous waterfall, a gigantic plume gushing out of the cliff face. Further on he climbed the remote valley of the Hérisson, where the river plunges over precipices, losing his way three times and stumbling among icy rocks in the dark in danger of his life. On 27 April he reached Switzerland at La Cure and found himself looking down on Lake Geneva and Mont Blanc, a view so overwhelming that he had to turn away. He lost 15 francs at petits chevaux in Geneva, hated the town and walked back along the lakeshore to Nyon. By this stage he was in poor shape, suffering from his supposedly gouty feet and from pains in chest and stomach. A doctor suggested a sanatorium at La Ligniére near Gland, a few miles further on. La Lignière is not mentioned in Harold's published account of his walk, but he stayed there for a week, undergoing fomentations, massage, scotch douches, hot baths, electric lightbaths, sun baths and other treatments. Health foods made on the premises were a speciality, and all meals were vegetarian. To begin with he felt worse, but the peacefulness of the place soon began to take effect. The sanatorium was …

Harold decided his own search would start with a `pilgrimage', a journey of the soul through snow and hard weather to the ever returning spring. He would walk to Italy, the land Maurice had dreamed of, hoping the rigours of the way would clear his mind and help him to see his own and the world's `great wonderful future'. And in some strange way it worked. His old life of social conformism, sexual pretence and literary pastiche was left behind forever. He made final preparations in Paris, sending his heavy luggage ahead to Milan and arranging for mail to be forwarded to post offices along his route. After much repacking he got his knapsack down from 21 lb. to 15 lb., reluctantly leaving out More's Utopia and Keats but keeping Shakespeare and Emerson.1

He also took his diary, intending to use it for some sort of publication later. A photograph taken before another of his long walks a year or two later shows him dressed most uncomfortably by today's standards, equipped with only a walking stick and rain cape (Plate 10). He probably looked much the same when he left Paris, ready for a walk of nearly 600 miles. He decided to let his beard grow as a gesture of liberation. The walk began from Paris on 1 April 1908. He made for Fontainebleau, where he spent three days, his mother arriving on the 5th to fuss over him and sew on missing buttons. For the next few weeks he walked steadily south-east, averaging some fifteen miles a day, often in rain. He preferred roads to rough country, enjoying the freedom to look around him and keep up a regular stride. Cars were still rare, but when motorists passed they stared in puzzled amusement, France having not taken up the new German-Swiss fashion for hiking. The further he went from Paris the kinder people became, but the more they regarded him as a lunatic. Sometimes a boy would trot along beside him, asking questions; once he was checked by the police. In the mornings he often wrote for several hours, but then he would walk without pausing except for a lunch break, unless the weather was especially bad. Occasionally even lunch was omitted, and he would fast for ten hours or more, convinced it did him good. Sometimes he walked on until the moon rose; it was by moonlight that he entered the hilltop `dream-city' of Flavigny, silent within its ancient walls, and slept on the inn landing, pestered by fleas. Many of the villages and little towns had medieval gates and splendid churches; often some great spire or ruined castle would seem to dominate the horizon all day. The hotels were cheap, damp and grubby, but they provided friendly company in the evenings, when mill hands, railway porters, commercial travellers and soldiers would tell him about poverty in France and ply him with too much wine. When spring broke among the vineyards of the Côte d'Or with a flourish of butterflies and the sound of a cuckoo, he felt `the first thrill, that vernal quickening of the blood, . . . the most beautiful sensation of the year'. People kept warning him of brigands, so at Dijon he bought a revolver, soon cursing its useless weight. As he approached the high plateau of the Jura the weather reverted to winter, with some snow. Locals suggested a diversion to Baume-les-Messieurs to see the caves and a genuine hermit; a storm trapped him there for two nights, swelling the famous waterfall, a gigantic plume gushing out of the cliff face. Further on he climbed the remote valley of the Hérisson, where the river plunges over precipices, losing his way three times and stumbling among icy rocks in the dark in danger of his life. On 27 April he reached Switzerland at La Cure and found himself looking down on Lake Geneva and Mont Blanc, a view so overwhelming that he had to turn away. He lost 15 francs at petits chevaux in Geneva, hated the town and walked back along the lakeshore to Nyon. By this stage he was in poor shape, suffering from his supposedly gouty feet and from pains in chest and stomach. A doctor suggested a sanatorium at La Ligniére near Gland, a few miles further on. La Lignière is not mentioned in Harold's published account of his walk, but he stayed there for a week, undergoing fomentations, massage, scotch douches, hot baths, electric lightbaths, sun baths and other treatments. Health foods made on the premises were a speciality, and all meals were vegetarian. To begin with he felt worse, but the peacefulness of the place soon began to take effect. The sanatorium was …

The Mountain and the Tower 1909 - 11

You are my chosen comrade, I am

yours.

We will erect of consecrated hours . . .

A temple to the universal soul.

Let us depart for where the sweet airs flow

Body and mind as one together grow

There in the forest by the mountain stream . . .

We will erect of consecrated hours . . .

A temple to the universal soul.

Let us depart for where the sweet airs flow

Body and mind as one together grow

There in the forest by the mountain stream . . .

('Invitation')

It

was appropriate, perhaps essential, to Harold's divided self that

his Continental pilgrimage paused in two very different centres of

freedom, one for the mind and one for the body. He discovered the

mountain first, windswept and comfortless, fit for Supermen, a place

of self-discipline and hard work. Then he or rather Maurice found

the tower, a medieval one in Florence, the city of aesthetic and

sensual delight.

For a while he shuttled between these two homes, as though they represented the two poles of his own personality, until spirit and flesh came briefly together in the Utopian relationship he needed. There would have been no Poetry Bookshop without this double experience in Ticino and Tuscany. The significance of the Lake Maggiore area for an idealist lay not in Locarno but in the mountain foothills above the nearby fishing village of Ascona. The Swiss canton of Ticino was a symbolic borderland between northern intellect and southern passion, free from both Teutonic overregulation and Latin anarchy. Wells had made it the gateway to his Utopia, and many free-thinkers had been drawn there, including a Belgian, Henri Oedenkoven, who had arrived in1900 and bought a hilltop behind Ascona, naming it Monte Verità, the Mountain of Truth. It was Monte Verità and its associated colony that had made Ascona famous, especially among the sort of people who frequented places like La Lignière and Waidberg.

Oedenkoven ran his magic mountain as a hotel where guests could undergo cures while living in harmony with the elements. He built simple `light and airhuts', sun baths, and small houses for longer-term residents, and named parts of the estate Parsifal Meadow, Valkyrie Cliffs in homage to Wagner, who, with Nietzsche, was the inspiration for much of the new age's thinking. Food was vegetarian, raw wherever possible, and clothes were minimal or dispensed with altogether. Photographs show guests dancing in the woods and working in the vegetable garden (Plates 11, 12). Harold must have visited Monte Verità soon after arriving at his Locarno chalet. Most of what he saw would have been familiar to him from Waidberg, but there was a more extreme colony in the woods beyond the compound. Some of Oedenkoven's original companions had deplored his commercialism and withdrawn to live as children of nature, obeying only one law, to be true to oneself and the earth. Nowhere else in Europe, perhaps, was there so much of that `simplification of life' which Harold had lectured about to the Haslemere socialists just before starting his long walk.

Visitors to Ascona ranged from city-dwellers taking brief health-cures to long-haired mystics and anarchists, drifting in from all over Europe in search of freedom. Not everyone was impressed. An Austrian aristocrat in about 1907was revolted at the sight of ill-washed, naked figures capering in the moonlight, scrawny from their diet of cabbage-water and raw turnips; having expected to find rampant sexuality, he decided the commune had in fact developed an unhealthy apathy towards sex, and he was glad to get back to the world of beefsteaks and long skirts.

Other guests were less sceptical, especially Germans at odds with the militaristic culture of their homeland (the language of the mountain was predominantly German, which was no barrier to Harold). The local villagers, all Italian-speaking, were suspicious, and their descendants still remember the colonists as matti, mad ones; but Switzerland was a uniquely tolerant society. The colonists believed their attitude to sex was healthy and natural, free from ‘civilised’ titillation. From 1905 the Munich psychoanalyst Otto Gross became a dominant influence, preaching his gospel of erotic liberation; regarded as dangerous by both the police and orthodox practitioners, he maintained that analysis was a means to inner and outer revolution, overthrowing the ego by releasing deeper forces to reshape the mind. He had been treated by Jung in Zurich earlier in 1908, a crucial year in the history of analysis; Harold may have heard of him there, and perhaps went to Ascona to learn more. During the next few years, there were rumours of Asconan orgies in which Gross encouraged people to act out their fantasies. His name is not well known to British readers, but some of his ideas are: in 1907 he had a passionate affair with Frieda Weekley, the German wife of an English professor (Gross told her she was `the woman of the future'), and when she left her husband in 1912 for …

For a while he shuttled between these two homes, as though they represented the two poles of his own personality, until spirit and flesh came briefly together in the Utopian relationship he needed. There would have been no Poetry Bookshop without this double experience in Ticino and Tuscany. The significance of the Lake Maggiore area for an idealist lay not in Locarno but in the mountain foothills above the nearby fishing village of Ascona. The Swiss canton of Ticino was a symbolic borderland between northern intellect and southern passion, free from both Teutonic overregulation and Latin anarchy. Wells had made it the gateway to his Utopia, and many free-thinkers had been drawn there, including a Belgian, Henri Oedenkoven, who had arrived in1900 and bought a hilltop behind Ascona, naming it Monte Verità, the Mountain of Truth. It was Monte Verità and its associated colony that had made Ascona famous, especially among the sort of people who frequented places like La Lignière and Waidberg.

Oedenkoven ran his magic mountain as a hotel where guests could undergo cures while living in harmony with the elements. He built simple `light and airhuts', sun baths, and small houses for longer-term residents, and named parts of the estate Parsifal Meadow, Valkyrie Cliffs in homage to Wagner, who, with Nietzsche, was the inspiration for much of the new age's thinking. Food was vegetarian, raw wherever possible, and clothes were minimal or dispensed with altogether. Photographs show guests dancing in the woods and working in the vegetable garden (Plates 11, 12). Harold must have visited Monte Verità soon after arriving at his Locarno chalet. Most of what he saw would have been familiar to him from Waidberg, but there was a more extreme colony in the woods beyond the compound. Some of Oedenkoven's original companions had deplored his commercialism and withdrawn to live as children of nature, obeying only one law, to be true to oneself and the earth. Nowhere else in Europe, perhaps, was there so much of that `simplification of life' which Harold had lectured about to the Haslemere socialists just before starting his long walk.

Visitors to Ascona ranged from city-dwellers taking brief health-cures to long-haired mystics and anarchists, drifting in from all over Europe in search of freedom. Not everyone was impressed. An Austrian aristocrat in about 1907was revolted at the sight of ill-washed, naked figures capering in the moonlight, scrawny from their diet of cabbage-water and raw turnips; having expected to find rampant sexuality, he decided the commune had in fact developed an unhealthy apathy towards sex, and he was glad to get back to the world of beefsteaks and long skirts.

Other guests were less sceptical, especially Germans at odds with the militaristic culture of their homeland (the language of the mountain was predominantly German, which was no barrier to Harold). The local villagers, all Italian-speaking, were suspicious, and their descendants still remember the colonists as matti, mad ones; but Switzerland was a uniquely tolerant society. The colonists believed their attitude to sex was healthy and natural, free from ‘civilised’ titillation. From 1905 the Munich psychoanalyst Otto Gross became a dominant influence, preaching his gospel of erotic liberation; regarded as dangerous by both the police and orthodox practitioners, he maintained that analysis was a means to inner and outer revolution, overthrowing the ego by releasing deeper forces to reshape the mind. He had been treated by Jung in Zurich earlier in 1908, a crucial year in the history of analysis; Harold may have heard of him there, and perhaps went to Ascona to learn more. During the next few years, there were rumours of Asconan orgies in which Gross encouraged people to act out their fantasies. His name is not well known to British readers, but some of his ideas are: in 1907 he had a passionate affair with Frieda Weekley, the German wife of an English professor (Gross told her she was `the woman of the future'), and when she left her husband in 1912 for …

Aus einem Blog:

Monro then set out on the walk from Paris to Milan

described in his Chronicle of a Pilgrimage (1909), the prelude to

three years abroad, mostly spent in Florence and the freethinking

community at Monte Verità, Ascona. Psychoanalysed in Zürich in

1908, he seems to have accepted that he was homosexual and that

his marriage was beyond rescue. The separation became permanent,

ending in divorce in 1916.

Few British people can have experienced so much of the alternative lifestyles that were being tried out on the continent. Monro's Before Dawn: Poems and Impressions (July 1911) declares boundless faith in the future, advocating sexual and social freedom, Wellsian socialism, and the Nietzschean ideal of the superman living at one with the earth.

Few British people can have experienced so much of the alternative lifestyles that were being tried out on the continent. Monro's Before Dawn: Poems and Impressions (July 1911) declares boundless faith in the future, advocating sexual and social freedom, Wellsian socialism, and the Nietzschean ideal of the superman living at one with the earth.

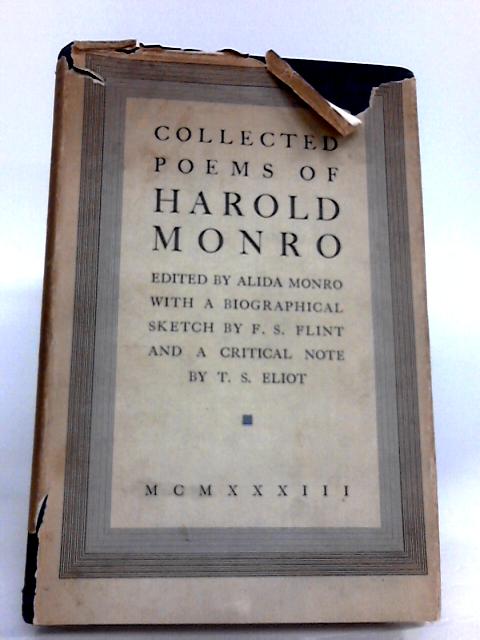

Mehr über Monro erfahren wir aus dem Buch von Dominic Hibberd: ‚Harold Monro. Poet of the New Age‘. Palgrave, New York 2001, das sich auf Beiträge von Harald Szeemann und Heiner Hesse stützt.

Darin

wird das bekannte Photo am Wasserfall abgebildet und näher bezeichnet

als „below

Harold’s mill“. Demnach

wurde die Hessemühle (unter diesem Namen fasse ich die beiden Mühlen

von Ronco zusammen) nicht nur von Hans Brandenburg, Mary Wigman,

Rudolf von Laban, Otto Gross, Erich Mühsam, Johannes Nohl, Ernst

Frick, Frieda Gross, Heinrich Goesch, Jakob Scheidegger, Franz Blazek,

Anton Faistauer, Robin Christian Andersen, Richard Seewald, Emil

Szittya, Friedrich Glauser, Bruno Goetz, Jakob Flach, Heiner Hesse und

so vielen anderen bewohnt sondern auch von dem englischen Poeten

Harold Monro. Eine Zuflucht für die Aussenseiter der Gesellschaft, ein

Ort der Maler, der Dichter und der Tänzer. Monros Gang nach Ascona war

eine pilgrimage to freedom.