|

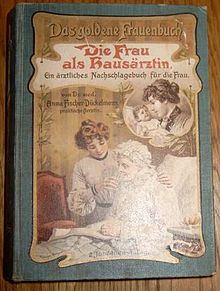

| Die Frau

als Hausärztin |

| Wikipedia | | Alternative medicine and reform strategies

made Anna Fischer-Dückelmann a most controversial, notorious, and

widely read women doctor before World War I, Paulette Meyer, english |

| PDF

|

Anna

Fischer-Dückelmann kam 1913 auf den Monte Verità, erwarb

dort Grundstück und Haus. Sie war die bekannteste Naturärztin

ihrer Zeit, eine Pionierin in diesem Feld. Ihr tausendseitiges Buch

‚Die Frau als Hausärztin’ war ein Bestseller,

erschien in Millionen-Auflagen, und stand, wie es heißt, in

jedem zweiten Haushalt. Schon 1914 waren ihre Schriften in 13

Sprachen übersetzt. Dabei hatte sie erst mit 33 Jahren, als

Mutter von drei Kindern, mit dem Studium der Medizin begonnen.

Ziel

ihres Buches

war, die Frauen und Mütter von der Schulmedizin und von den

Ärzten überhaupt möglichst unabhängig zu machen.

Sie bot damit erstmals speziell den Frauen ein Grundwissen in

Naturheilkunde und Sexualaufklärung und damit ein Stück

Emanzipation. Nicht männliche Ärzte, Ärztinnen  sollten

die Frauen behandeln. Eine gesunde Lebensweise ohne Fleisch, Alkohol

und Nikotin sollte viele Krankheiten erst gar nicht aufkommen

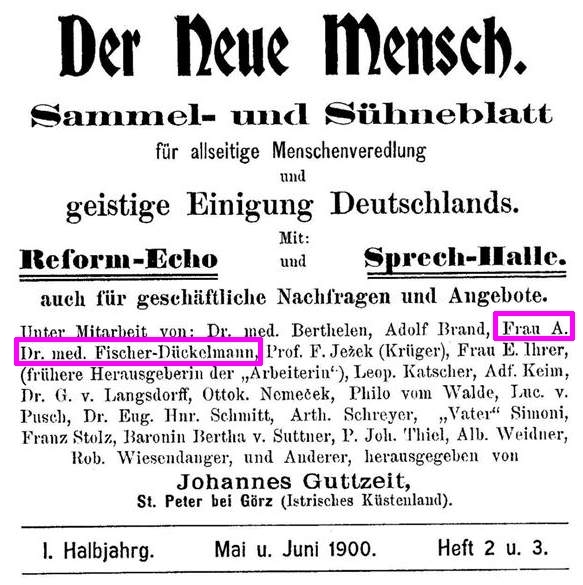

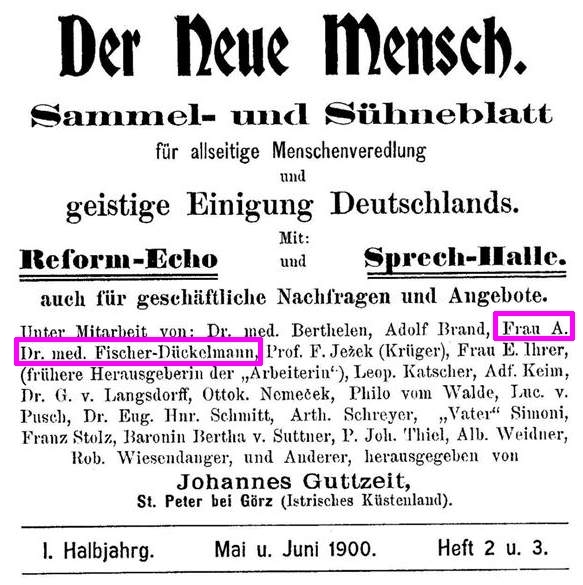

lassen. Schon um 1900 hatte sie, zusammen mit Karl Wilhelm

Diefenbach und der

Pazifistin Bertha von Suttner in der Zeitschrift ‚Der Neue

Mensch’ des Naturpredigers Johannes Guttzeit geschrieben. Guttzeit war um die selbe Zeit einer der Lehrmeister von Gusto

Gräser. Es versteht sich, dass die aufgeklärte Naturheilerin von der etablierten männlichen Schulmedizin als

„Quacksalberin“ und „Krebsgeschwür“ angefeindet wurde. Dass Gusto Gräser die Mitkämpferin Dückelmann

aufgesucht hat, ist wahrscheinlich sollten

die Frauen behandeln. Eine gesunde Lebensweise ohne Fleisch, Alkohol

und Nikotin sollte viele Krankheiten erst gar nicht aufkommen

lassen. Schon um 1900 hatte sie, zusammen mit Karl Wilhelm

Diefenbach und der

Pazifistin Bertha von Suttner in der Zeitschrift ‚Der Neue

Mensch’ des Naturpredigers Johannes Guttzeit geschrieben. Guttzeit war um die selbe Zeit einer der Lehrmeister von Gusto

Gräser. Es versteht sich, dass die aufgeklärte Naturheilerin von der etablierten männlichen Schulmedizin als

„Quacksalberin“ und „Krebsgeschwür“ angefeindet wurde. Dass Gusto Gräser die Mitkämpferin Dückelmann

aufgesucht hat, ist wahrscheinlich

aber nicht belegbar. Er kam 1911

im Pferdewagen mit seiner Familie nach Dresden, wo Fotoaufnahmen

gemacht wurden. 1925/26 wohnte er in der Nähe des Dresdner

Hauses von Fischer-Dückelmann, dem sogenannten „Artushof“ in

Loschwitz. Die Tochter der Naturärztin setzte damals deren

publizistische Arbeit in aufopferungsvoller Weise fort.

Möglicherweise war es Gräser, der Anna Fischer zum Monte

Verità gelockt hat. aber nicht belegbar. Er kam 1911

im Pferdewagen mit seiner Familie nach Dresden, wo Fotoaufnahmen

gemacht wurden. 1925/26 wohnte er in der Nähe des Dresdner

Hauses von Fischer-Dückelmann, dem sogenannten „Artushof“ in

Loschwitz. Die Tochter der Naturärztin setzte damals deren

publizistische Arbeit in aufopferungsvoller Weise fort.

Möglicherweise war es Gräser, der Anna Fischer zum Monte

Verità gelockt hat.

In Ascona

betätigte sich Anna Fischer-Dückelmann im Sanatorium von

Oedenkoven als Ärztin und Wirtschaftsleiterin. Sie lockerte die

strengen Diätregeln und hoffte damit dem schwächelnden

Unternehmen wieder Auftrieb zu geben, blieb aber ohne Erfolg. Sie zog

sich bald wieder vom Sanatorium zurück, widmete sich im Krieg

besonders der Verwundetenpflege und starb 1917 auf dem Monte Verità.

|

Anna Fischer-Dückelmann als Modell

für die Locarneser Malerin

Clara Wagner-Grosch

The woman artist who drew the model from

life positioned the gymnast’s arm in front of

her face to provide anonymity. The signature of this

artist, Clara Wagner Grosch, included a notation that the portrait

was

done in Locarno. This was the

Italian Swiss city near the life-reform

colony of Ascona

where Fischer-Dückelmann worked from time to

time

as consulting

physician and vegetarian diet advisor. (85) In posing as her

own “healthy

woman” model, the physician would only be continuing

to draw upon

her own personal experiences, as she had testified to

doing in other

publications when giving other women preventative

hygiene advice.

When Fischer-Dückelmann recommended, for

example, that cities be

built so that

inhabitants could enjoy the greenery of gardens and trees,

she was

describing the type of suburb outside Dresden

where her family

lived in 1911.

Bad air, sleep-disrupting noises, and poor nutrition in

crowded city

tenements would be mitigated when all districts were

planned as such

“garden cities,” (86) she suggested; and poor, as well as

wealthy, families

needed to get back in touch with more natural environments,

including plants and

animals. The author was optimistic

enough to suggest

that the future would bring improvements even as

she criticized

contemporaries as being out of touch with the best in

ancient and rural

traditions.

While the physician criticized the

wealthier classes for lacking physical

exercise and for

being overly fed and poorly nourished by the rich food called in Germany das

gute Essen,

she also pointed out that women

of the impoverished working classes lacked

both nutritious food and

adequate rest while they worked first outside at

jobs and afterwards

inside the home serving their husbands and

families. Fischer-Dückelmann believed such women should be provided

vacations at rest homes

to recover while working class men who

laboured for 12-hour days also

needed more time for rest and recovery. (p.172)

Aus:

Physiatrie

and German Maternal

Feminism:

Dr. Anna Fischer-Dückelmann

Critiques Academic

Medicine:

PAULETTE

MEYER

Abstract. Alternative

medicine and reform strategies made Anna Fischer-Dückelmann a most controversial, notorious, and widely read women doctor before

World

War I. She published a dozen titles in 13

languages asserting that national

well-being depended on maternal prowess. To her critics, Fischer-Dückelmann’s

commitment to medical self-help and practices of Physiatrie amounted to medical quackery. Her career has been largely unexamined, yet her feminist

critiques

and social concerns are not far removed from modern social medicine. For

this

pioneering doctor, treating physical and emotional ills and promoting the health

of families were first steps toward healing the divisions of a world at

war.

Résumé. Les

approches alternatives et réformistes du docteur Anna Fischer-Dückelmann ont fait d’elle

une personne controversée, connue et beaucoup

lue

dans les années qui ont précédé la Première Guerre Mondiale. Elle a en

effet

publié une douzaine d’ouvrages, qui ont été traduits dans 13 langues,

dans

lesquels elle soutenait que la santé, au niveau national, dépendait avant

tout

des mères. Aux yeux de ses critiques, sa foi dans l’automédication et dans

la

« physiatrie » relevait du charlatanisme. Sa carrière a été peu étudiée

jusqu’ici,

mais

il ressort que plusieurs de ses approches féministes et de ses préoccupations

sociales n’étaient pas très éloignées de ce qui caractérise aujourd’hui la

médecine

sociale. Pour cette femme-médecin pionnière, le traitement des maladies

et la promotion de la santé des familles constituaient les premiers pas

vers

la réconciliation de mondes en guerre.

Paulette Meyer,

PhD, Portland, Oregon.

“Maternal feminism” and “physiatrie” are terms

that describe Fischer-Dückelmann’s ideological standpoints. Maternal feminism refers

to her advocacy of women physicians to treat women, a stance that

placed her in conflict with much of the male medical establishment. She

defined physiatrie as the practice of healthful diet and lifestyle to prevent

disease. In her mind these included a vegetarian diet and abstinence

from alcohol, not especially popular notions in Imperial Germany. As a

contemporary of Franziska Tiburtius, Fischer-Dückelmann’s curiosity

and open-mindedness to alternative theories of treatment were condemned by many professional colleagues. This was not the type of attention sought by most women physicians. Just five years after Dr. Tiburtius’s Canadian message, the prestigious German medical journal

Münchener Medizinische

Wochenschrift published in July 1914 a disclaimer from an editor of a new medical publication called Dia. The irate

editor, Dr. Adolf Braun, claimed that an announcement in his first issue

advertising Frau Dr. Fischer-Dückelmann’s books was hidden in a location where he was not able to read it until after publication. He opposed

the woman physician’s works as quackery and vowed to remove future

reference to her books in order to preserve the purity of his “physician-loyal” publication. If it were not possible to avoid paid advertisements of

such quack medicine, he would certainly resign as editor of Dia. By the

time Braun’s disclaimer was published, Fischer-Dückelmann had sold

over a million copies of her publications, which may have made her

unpopular with less successful colleagues and literary competitors. In

1910,

when another woman physician, Jenny Springer (MD Zürich,

1897),

published her own medical guidebook (The

Woman Doctor of the

House), reviewers expressed the wish that this

publication would displace the “lamentably wide popularity of the books by F…D…” linking

Fischer-Dückelmann

to the “cancerous spread of quackery.”

Physiatrie and German Maternal Feminism

147

By

1914 Anna Fischer-Dückelmann had published

a dozen popular

medical titles translated into 13 languages, including English. Combining

simple explanations of current medical knowledge with descriptions of

alternative or traditional medical practices, she gained the admiration of

her lay audience and the censure of many professional peers. Her 1000-page medical advice book sold over a million copies in German alone in

its first 12 years of publication. She instructed nursing students in Dresden, Germany,

taught home nursing skills to international students in

Switzerland, and also practised medicine at health spas where she

demonstrated dietary modifications and participated in gymnastic training and water therapies along with her students and patients. Integrating popular healing traditions into academic medicine made her reputation among medical reformers in Europe and North

America.

Her

personal perspectives were that of an outsider, first of all, as a

woman physician in a country that had long refused to allow females to

take medical certification examinations. She was also an Austrian immigrant to Imperial Germany and she earned her medical degree over the

border in Switzerland.

Fischer-Dückelmann moved in from the margins

of her society—to use bell hook’s characterisation —and asserted a

maternal feminist authority to refashion the German men’s medical profession. Feminist Hedwig Dohm had responded to the patronizing attitude of many German physicians: “What if…indeed women were indiscriminately sick, sick; nothing but a great wound in the universe; and we

poor invalids in spite of ourselves would really do best—as the wounded

animal creeps into a thicket—to vanish within the nursery, the bed-chamber, the lying-in chamber, giving ourselves up solely to the culture

of our sex-functions.”

The

patriarchal characterization of women is

what prompted Anna

Fischer-Dückelmann

to earn a medical degree

and publish information that women and their families might use to

counter such views.

Physiatrie and German Maternal

Feminism

149

(Im Internet)

|

sollten

die Frauen behandeln. Eine gesunde Lebensweise ohne Fleisch, Alkohol

und Nikotin sollte viele Krankheiten erst gar nicht aufkommen

lassen. Schon um 1900 hatte sie, zusammen mit Karl Wilhelm

Diefenbach und der

Pazifistin Bertha von Suttner in der Zeitschrift ‚Der Neue

Mensch’ des Naturpredigers Johannes Guttzeit geschrieben. Guttzeit war um die selbe Zeit einer der Lehrmeister von Gusto

Gräser. Es versteht sich, dass die aufgeklärte Naturheilerin von der etablierten männlichen Schulmedizin als

„Quacksalberin“ und „Krebsgeschwür“ angefeindet wurde. Dass Gusto Gräser die Mitkämpferin Dückelmann

aufgesucht hat, ist wahrscheinlich

sollten

die Frauen behandeln. Eine gesunde Lebensweise ohne Fleisch, Alkohol

und Nikotin sollte viele Krankheiten erst gar nicht aufkommen

lassen. Schon um 1900 hatte sie, zusammen mit Karl Wilhelm

Diefenbach und der

Pazifistin Bertha von Suttner in der Zeitschrift ‚Der Neue

Mensch’ des Naturpredigers Johannes Guttzeit geschrieben. Guttzeit war um die selbe Zeit einer der Lehrmeister von Gusto

Gräser. Es versteht sich, dass die aufgeklärte Naturheilerin von der etablierten männlichen Schulmedizin als

„Quacksalberin“ und „Krebsgeschwür“ angefeindet wurde. Dass Gusto Gräser die Mitkämpferin Dückelmann

aufgesucht hat, ist wahrscheinlich

aber nicht belegbar. Er kam 1911

im Pferdewagen mit seiner Familie nach Dresden, wo Fotoaufnahmen

gemacht wurden. 1925/26 wohnte er in der Nähe des Dresdner

Hauses von Fischer-Dückelmann, dem sogenannten „Artushof“ in

Loschwitz. Die Tochter der Naturärztin setzte damals deren

publizistische Arbeit in aufopferungsvoller Weise fort.

Möglicherweise war es Gräser, der Anna Fischer zum Monte

Verità gelockt hat.

aber nicht belegbar. Er kam 1911

im Pferdewagen mit seiner Familie nach Dresden, wo Fotoaufnahmen

gemacht wurden. 1925/26 wohnte er in der Nähe des Dresdner

Hauses von Fischer-Dückelmann, dem sogenannten „Artushof“ in

Loschwitz. Die Tochter der Naturärztin setzte damals deren

publizistische Arbeit in aufopferungsvoller Weise fort.

Möglicherweise war es Gräser, der Anna Fischer zum Monte

Verità gelockt hat.